When math lessons at a goat farm beat sitting behind a desk

Wess Wheeler (L), an independent learning opportunity student at Randolph Union High School, and Miles Hooper, manager and co-owner of Ayers Brook Goat Dairy farm, among the goats.

RANDOLPH, Vt. — Miles Hooper, the 26-year-old manager of Vermont’s largest goat farm, remembers what it’s like to be 16 and not want to be in a classroom. Just 10 years ago, he was kicked out of his Vermont public school and finished at an alternative high school in Maine.

That’s why Hooper identifies with Wessley “Wess” Wheeler, the sophomore spending two afternoons a week at Ayers Brook Goat Dairy farm through a program that lets high school students in this rural town earn academic credit via hands-on work.

“Fortunately, I had the wherewithal to figure out I’m smart in other ways,” Hooper recalls, then stops suddenly, remembering something.

“Crap, I forgot to switch out the milk in the pasteurizer,” he says, before sprinting for the barn, Wess hurrying behind him. Miles moves the milk, and they’re off again, charging past pens of goats leaping up to greet them as they pass.

A minute later, Miles is checking if there’s enough detergent and acid to clean the milk tank after Vermont Creamery finishes collecting the day’s milk. When the tank is empty, he whips out a calculator, and does the math. He sold 8,405 pounds of milk at 55 cents a pound — that’s $4,623 for the day.

Here at the farm, there’s no curriculum, but math and science lessons are all around you, and there’s always a problem to solve. For Wess, who has ADHD and struggles with textbook math, the five hours he spends here each week are a welcome break from the confines of his classroom at Randolph Union, the 374-student middle and high school he attends a half-mile away.

“It’s better to be out here than sitting behind a desk listening to a teacher talk,” Wess says. “Here, I get to do things.”

Such hands-on work is just one way students at Randolph Union gain real-life experience and exposure to careers in their communities. Field trips to local employers are another. It’s all part of a statewide push to “personalize” learning, giving students more of a say over what — and where — they study. The effort has two chief goals: keeping students engaged in school and keeping them in the state after they graduate.

Vermont has one of the oldest populations in the United States and, the Vermont State Data Center reports, is now tied with Connecticut for the lowest birth rate in the nation. If the state doesn’t find a way to hold on to its shrinking number of students — or persuade more workers to move to Vermont — it won’t be able to fill the jobs left vacant by retiring baby boomers, with more than 100,000 new job openings projected by 2024. The tax base will diminish, and the state will wind up with budget deficits.

That’s the “doomsday scenario” Vermont is trying to avoid through programs like Randolph Union’s, says Joan Goldstein, the state’s commissioner of economic development. She is part of a statewide campaign aimed at convincing former residents to return and visitors to stay.

In fact, the Green Mountain state is so eager to grow its population that it’s offering up to $10,000 a year to new residents who work remotely for an out-of-state employer.

It’s better to be out here than sitting behind a desk listening to a teacher talk.

But Goldstein, who helped create a hands-on manufacturing course at Randolph Union in 2014, says “retention is much easier than recruitment.” And work-based learning, she says, helps students see “that there are opportunities here, that they don’t have to leave” to find good jobs.

There are other potential benefits, too. Getting students out into the community could help bridge the growing divide between Vermont’s public schools and the aging taxpayers who finance them, says Elijah Hawkes, Randolph Union’s principal.

“Either you fund programs that connect with the community, or the community isn’t going to fund your school,” he says.

It’s not just Vermont that is embracing work-based learning. Programs that let students try on careers before they graduate are catching on across the country, as parents, policymakers and employers demand “more relevance and more real-world skills” from the nation’s high schools, says Kate Blosveren Kreamer, deputy executive director of Advance CTE, a nonprofit representing state directors of career and technical education.

“Coming out of the recession, there is a real hunger for real-world skills,” says Kreamer.

A curious goat at Ayers Brook Goat Dairy farm.

But making work-based learning work isn’t easy. It requires school districts to build new relationships with local employers; develop novel ways of measuring student growth and awarding academic credit; and navigate a thicket of logistical challenges — from arranging transportation to managing liability. For most educators, it’s a cultural shift, and one that comes with additional, often uncompensated, work.

Then there is the issue of quality control. Monitoring rigor in a classroom isn’t that complicated; maintaining it across multiple worksites is trickier.

Given these hurdles, most schools are starting small. At Randolph Union, there are 32 students participating in “independent learning opportunities,” or ILOs, and another six in a course that introduces students to careers in water management.

The challenge that rural high schools like Randolph Union now face is how to scale work-based learning so that more students like Wess see the connections between the classroom and a career, and maybe — just maybe — see a future in their graying home state.

Vermont’s experiment in experiential learning goes back a number of years, but it took off in 2013, when the legislature passed a law that lets students meet state graduation standards through work-based experiences. That law, known as Act 77, “opened up learning beyond the four walls of the traditional classroom,” says John Fischer, who was a deputy secretary of the Vermont Agency of Education at the time. “It recognized that learning can occur anywhere.”

Among Act 77’s aims: to reduce high school dropout rates, particularly among low-income students. (In Vermont in 2013 18 percent of economically disadvantaged students dropped out of high school compared to only 3.5 percent of non-disadvantaged students.)

“We knew we had an equity problem,” Fischer recalls. “Some students were learning well in a traditional classroom, and for others, it wasn’t working for them.”

But implementation of Act 77 has been uneven, raising new equity concerns among advocates. While some districts have hired work-based-learning coordinators to help place students in positions, others have leaned on teachers and guidance counsellors “to make the magic happen,” says Juliette Longchamp, professional programs director at Vermont-NEA (the state’s teachers union).

We knew we had an equity problem. Some students were learning well in a traditional classroom, and for others, it wasn’t working for them.

Longchamp worries that some schools are adding to the burden on teachers while doing little to ensure the quality of students’ job placements.

“If we really care that regardless of what zip code you live in you have equal opportunity, that’s definitely not happening,” she says.

Part of the problem may be that even getting a work-based program going can be difficult. Last year, the University of Vermont worked with five high schools to create classes based in their communities. Two of the programs took off; three floundered.

The difference, says Jane Kolodinsky, who led the pilot as chair of the university’s Community Development and Applied Economics Department, was partly in the level of commitment from teachers and administrators.

“There has to be buy-in from the bottom up and the top down,” she says.

Success also requires employers and administrators who are willing to take risks and tackle logistical challenges together, Goldstein says.

“You need pioneers who will raise their hands and say ‘we’re going to figure this out,’ ” she says.

At Randolph Union, the pioneer — the “pied piper,” as Goldstein calls him — is Ken Cadow, a former Navy lieutenant and grocery store owner who was given a 2017 Champion award by the Vermont Agency of Education and the New England Secondary School Consortium for his efforts in workforce development and personalized learning.

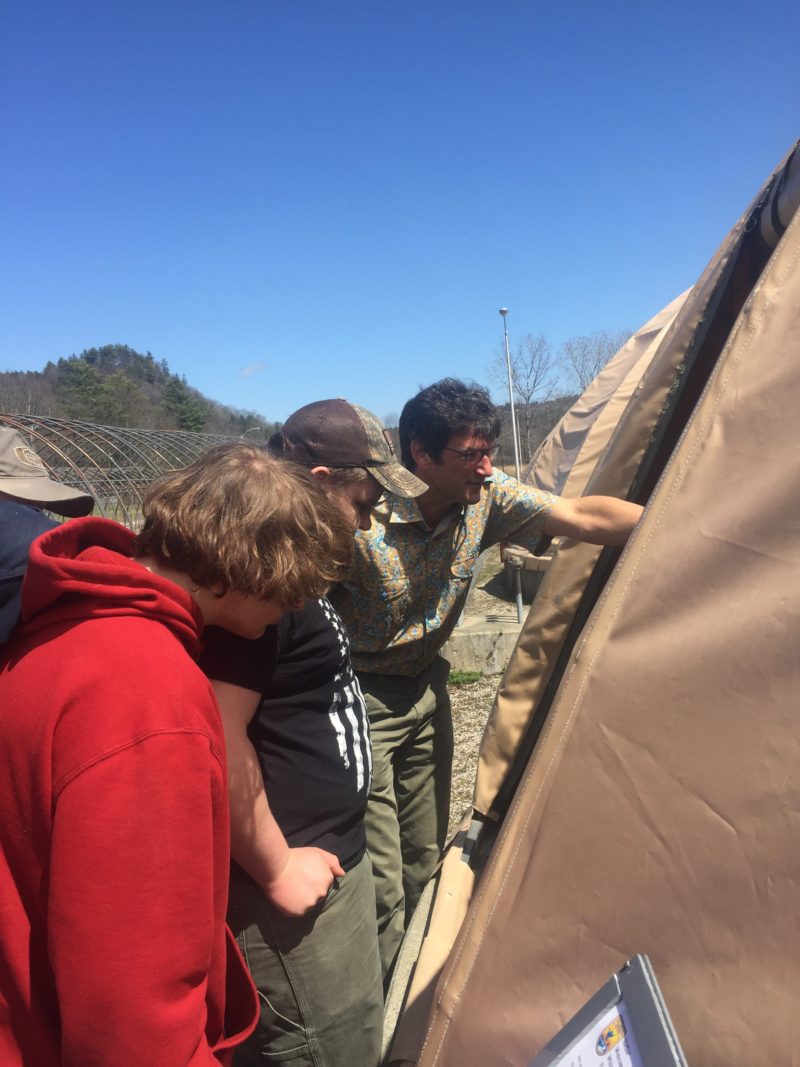

Ken Cadow, director of Career Pathways and Workforce Development at Randolph Union High School, points out fish to students in his water management course during a fish hatchery tour.

A tall, thin man who is partial to vibrantly patterned short-sleeved shirts, Cadow talks fast and walks faster, as if perpetually late for an important meeting.

Cadow says he “stumbled into education” as a substitute teacher when he moved to Vermont 15 years ago and was “struck by the fact that there was no real thought as to what these kids would do next.”

“It was very focused on graduation,” Cadow says. “They would graduate and have the rug pulled out from under them.”

Cadow believes schools should show students the relevance and utility of what they’re learning in the classroom and connect them to careers that make use of their skills and interests. So when Goldstein came looking for a school to copy a New Hampshire work-based program five years ago, Cadow raised his hand.

The result was the School of Tech, a semester-long course in which students divide their time between the classroom and local manufacturer GW Plastics, learning every stage of production, from concept to marketing. They also get lessons in professionalism and intergenerational teamwork — “soft skills” that employers say recent graduates lack. A second course, the one focused on water management, followed three years later. Cadow calls his model “the deployed classroom.”

Around the same time, Cadow met Gus, a freshman who was so bored by school that he was planning to drop out and be home-schooled. He learned that Gus was a passionate goat farmer, who was rising at 4 a.m. each morning to care for his animals.

Cadow didn’t want Gus to miss out on the social aspects of school, so he offered him a deal: Come to school for six hours a week, and you can spend the rest of the time on the farm. We’ll give you math and English credits for writing a business plan; biology credit for studying antibiotics and breeding; and social studies credit for researching how Vermont’s policies affect goat farmers.

That was the beginning of Randolph Union’s ILOs, which let students pursue their passions outside of school and get academic credit for it. This year, there are students engaged in everything from high-end woodworking to bioengineering plants.

Some students, like Wess, spend only a few hours each week outside school; others check in monthly, if that frequently. Many take the freedom seriously; a few “blow it off and watch Netflix,” says Rafe Sauer, 17, a junior who has started a business selling spalted maple cutting boards and bowls.

ILOs are the ultimate in personalized learning, and they depend on teachers to structure programs, assess student growth and award academic credit. In other words, they’re more work for teachers.

At Randolph Union, there’s been some pushback from teachers who have been asked to oversee multiple ILOs. This year, the school modified the contracts of three teachers to include time to support independent learning. Cadow hopes to grow the program to the point at which one teacher in each content area is devoted to ILOs.

“If enough students do it, it’s a shift in resources, not necessarily an addition,” he says.

On a sign outside Randolph Union, there’s a message that reads: “Some old-fashioned things, like fresh air and sunshine, are hard to beat.”

It’s raining at the Ayers Brook farm on this Tuesday in May, but fresh air is in abundance as Wess describes how he’s used fractions to calculate how much feed to give each pen of goats.

“I see the importance of math, but you need to get out and do it” for it to make sense, he says.

When Kandy Wheeler arrives in her pickup truck to take her son home, she says Wess is more suited to the farm than the classroom.

“Wess is a hands-on learner. It’s hard for him to sit still,” she says.

It’s too soon to say if Vermont’s foray into personalized learning will help students like Wess stay engaged in school and on a path to college or career. Right now, the programs are reaching only a tiny fraction of the state’s students.

Coming out of the recession, there is a real hunger for real-world skills.

But there are some encouraging signs. Fewer low-income students statewide are dropping out of high school (down to 15.8 percent from 18 percent in 2013). And in Randolph, according to Hawkes, the four-year graduation rate has increased by twelve percentage points since the work-based program began in 2014, to 92 percent, three percentage points above the state average.

Whether the reforms will keep students anchored in the state is another question. According to the Vermont State Data Center, the state lost more than 2,400 residents in 2016, and the state’s Department of Labor reports that its population is expected to remain nearly flat over the next eight years.

In Randolph, Wess is keeping his options open. He’s considering staying in Vermont to farm, but he’s intrigued by Ohio, where he hears the hunting is good.

For now, all that matters to Kandy Wheeler is that her son is excited about learning.

“He comes home from the farm,” she says, “and he’s happy.”

Source: HechingerReport

Last Updated on 19 June 2024

We cover inequality and innovation in education with in-depth journalism that uses research, data and stories from classrooms and campuses to show the public how education can be improved and why it matters.