When math lessons at a goat farm beat sitting behind a desk

Last Updated on 30 September 2023

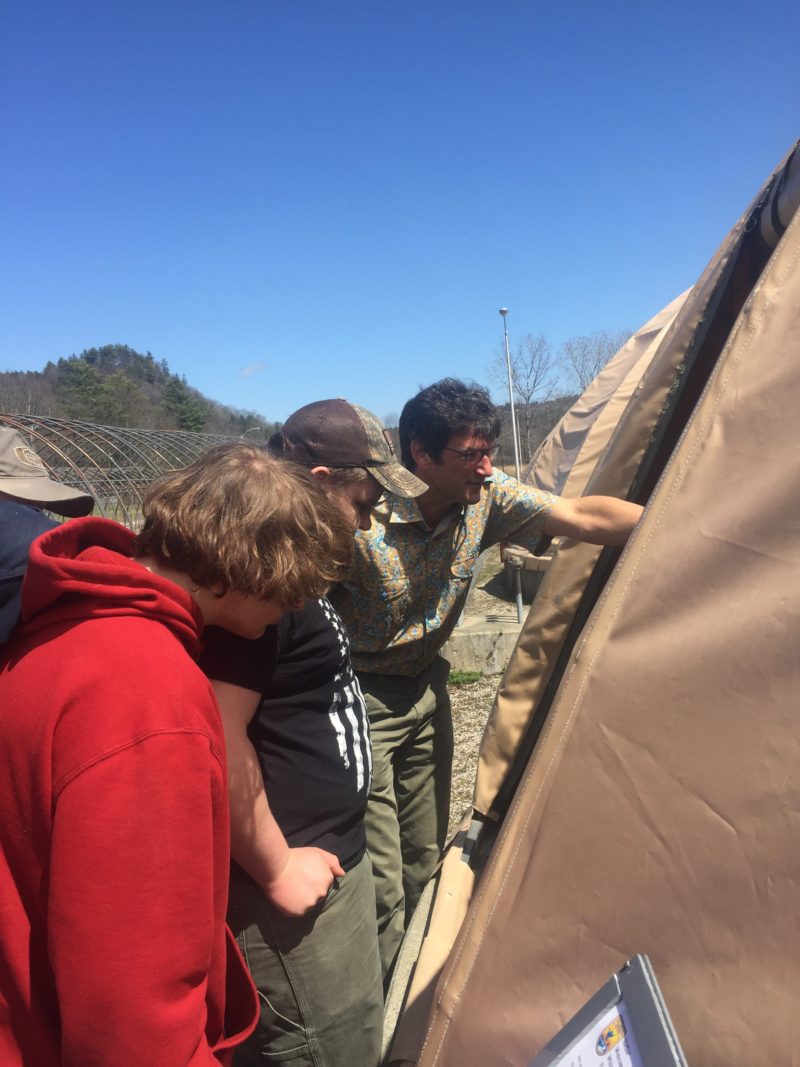

Ken Cadow, director of Career Pathways and Workforce Development at Randolph Union High School, points out fish to students in his water management course during a fish hatchery tour.

A tall, thin man who is partial to vibrantly patterned short-sleeved shirts, Cadow talks fast and walks faster, as if perpetually late for an important meeting.

Cadow says he “stumbled into education” as a substitute teacher when he moved to Vermont 15 years ago and was “struck by the fact that there was no real thought as to what these kids would do next.”

“It was very focused on graduation,” Cadow says. “They would graduate and have the rug pulled out from under them.”

Cadow believes schools should show students the relevance and utility of what they’re learning in the classroom and connect them to careers that make use of their skills and interests. So when Goldstein came looking for a school to copy a New Hampshire work-based program five years ago, Cadow raised his hand.

The result was the School of Tech, a semester-long course in which students divide their time between the classroom and local manufacturer GW Plastics, learning every stage of production, from concept to marketing. They also get lessons in professionalism and intergenerational teamwork — “soft skills” that employers say recent graduates lack. A second course, the one focused on water management, followed three years later. Cadow calls his model “the deployed classroom.”

Around the same time, Cadow met Gus, a freshman who was so bored by school that he was planning to drop out and be home-schooled. He learned that Gus was a passionate goat farmer, who was rising at 4 a.m. each morning to care for his animals.

Cadow didn’t want Gus to miss out on the social aspects of school, so he offered him a deal: Come to school for six hours a week, and you can spend the rest of the time on the farm. We’ll give you math and English credits for writing a business plan; biology credit for studying antibiotics and breeding; and social studies credit for researching how Vermont’s policies affect goat farmers.

That was the beginning of Randolph Union’s ILOs, which let students pursue their passions outside of school and get academic credit for it. This year, there are students engaged in everything from high-end woodworking to bioengineering plants.

Some students, like Wess, spend only a few hours each week outside school; others check in monthly, if that frequently. Many take the freedom seriously; a few “blow it off and watch Netflix,” says Rafe Sauer, 17, a junior who has started a business selling spalted maple cutting boards and bowls.

ILOs are the ultimate in personalized learning, and they depend on teachers to structure programs, assess student growth and award academic credit. In other words, they’re more work for teachers.

At Randolph Union, there’s been some pushback from teachers who have been asked to oversee multiple ILOs. This year, the school modified the contracts of three teachers to include time to support independent learning. Cadow hopes to grow the program to the point at which one teacher in each content area is devoted to ILOs.

“If enough students do it, it’s a shift in resources, not necessarily an addition,” he says.

On a sign outside Randolph Union, there’s a message that reads: “Some old-fashioned things, like fresh air and sunshine, are hard to beat.”

It’s raining at the Ayers Brook farm on this Tuesday in May, but fresh air is in abundance as Wess describes how he’s used fractions to calculate how much feed to give each pen of goats.

“I see the importance of math, but you need to get out and do it” for it to make sense, he says.

When Kandy Wheeler arrives in her pickup truck to take her son home, she says Wess is more suited to the farm than the classroom.

“Wess is a hands-on learner. It’s hard for him to sit still,” she says.

It’s too soon to say if Vermont’s foray into personalized learning will help students like Wess stay engaged in school and on a path to college or career. Right now, the programs are reaching only a tiny fraction of the state’s students.

Coming out of the recession, there is a real hunger for real-world skills.

But there are some encouraging signs. Fewer low-income students statewide are dropping out of high school (down to 15.8 percent from 18 percent in 2013). And in Randolph, according to Hawkes, the four-year graduation rate has increased by twelve percentage points since the work-based program began in 2014, to 92 percent, three percentage points above the state average.

Whether the reforms will keep students anchored in the state is another question. According to the Vermont State Data Center, the state lost more than 2,400 residents in 2016, and the state’s Department of Labor reports that its population is expected to remain nearly flat over the next eight years.

In Randolph, Wess is keeping his options open. He’s considering staying in Vermont to farm, but he’s intrigued by Ohio, where he hears the hunting is good.

For now, all that matters to Kandy Wheeler is that her son is excited about learning.

“He comes home from the farm,” she says, “and he’s happy.”

Source: HechingerReport

We cover inequality and innovation in education with in-depth journalism that uses research, data and stories from classrooms and campuses to show the public how education can be improved and why it matters.